Ashleigh Hill is a music lover that explores the mystic and magic behind the artistry in music and culture, working at the intersection of community, experiences, and media at TheFutureParty. She’s obsessed with live music, making it difficult to choose a favorite artist. However, she finds new music daily and has around 20 mixes on Spotify for your happy listening!

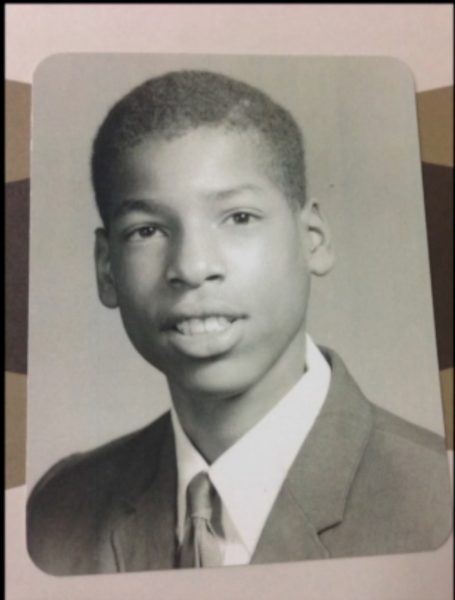

Cedric Walker is bright, kind, and beyond excited for life. As he says, “the ideas don’t stop!”. Living by the mentality which tour promoter Jack Nance stated, “In this business there’s no excuses. Every night from Thursday to Saturday, the Commodores need to be on stage at 8pm; your band needs to strike a note. Not at 7:59pm, not 8:01pm, and if you miss that time slot for any reason—go home.” Cedric didn’t miss that eight o’clock time slot once the entire tour, or his entire career. Cedric saw that as a promoter, he had to create products and most importantly, connect with the customer. This mentality of entrepreneurship beamed from the start, all starting with wanting to be a Cub Scout.

“I call myself one of the luckiest men in show business, or even in the world.”

Ashleigh Hill: Let’s kick it off with rewinding all the way back to the beginning of your story and where you’re from. Can you tell us a bit about you and your family?

Cedric Walker: I’m from Baltimore, Maryland, and I grew up in a home with my parents and three siblings. The entrepreneur in me came to life during Cub Scouts. When it came time for dues and it was five dollars a week, my father couldn’t afford it. So from that point on, I started doing things, shining shoes, my mother then taught me how to freeze Kool-Aid in cups and sell it to the kids. My grandfather made me my first shoeshine box. It was exciting because I learned that I could make $6 a day on shoes and $15 a week selling freezer cups. I gained my independence. We went door to door collecting for UNICEF. I was one of the top six kids in Baltimore City in collecting for UNICEF. So those kinds of things taught me that you can get out and do your thing.

AH: Your spirit was shown early—the entrepreneurial spirit that is—but also a philanthropic spirit. It definitely is a through point in your work, which I think is really special. How did you go from selling all these things and being a self-starter, to stage managing the Commodores and a Tour Marketing Director for Jackson Five?

CW: I call myself one of the luckiest men in show business, or even in the world. I went to Tuskegee to go to school and started working in my uncle’s night club washing dishes. It was a hole in the wall deep in the woods in Alabama. The Commodores were one of the live bands. I would volunteer to help the bands set up their equipment because I wasn’t 21 and that gave me a reason to get out of the kitchen, into the club, and around the girls. I would watch my uncle arrange different entertainment each week, then I would go out and pass out the flyers and help the bands set up. I tell people I volunteered my way into the business. The Commodores took me on the tour and they were the opening act for the Jackson Five. I would sit in the room with them and watch them put together the shows. I lived on the stage and in trucks. I didn’t ever go to my hotel. I mean, I helped load trucks—sound trucks, light trucks—it didn’t matter. In return, the technicians taught me lighting and sound. I wanted to learn. It was a playground of education. It was a great experience.

AH: Where did you make the shift from the Commodores to take the next step within the business?

CW: I loved the creativity of production, however one day I was setting up the stage at a big outdoor ‘Three Dog Night’ concert in Birmingham, Alabama. I got to know an older stage manager. He said, “Listen young man, I’m in my mid 50s and I’ve been a roadie all my life, it’s too grueling of a job to make a career of.” He told me you need to try to move away from this and create a future in the business if you love it. So at that point, I wanted to get away from stage and production management. My father told me I was crazy and it was my ego. But I didn’t listen. I left my job and started as a booking agent at a small agency in Atlanta, booking bands for college homecoming. And from there I was hired by a production company, Rowe productions. They trained me in marketing. I gained a lot of experience promoting in markets across the country and garnered the position of Marketing Director, promoting the national Jacksons Tour in 1979.

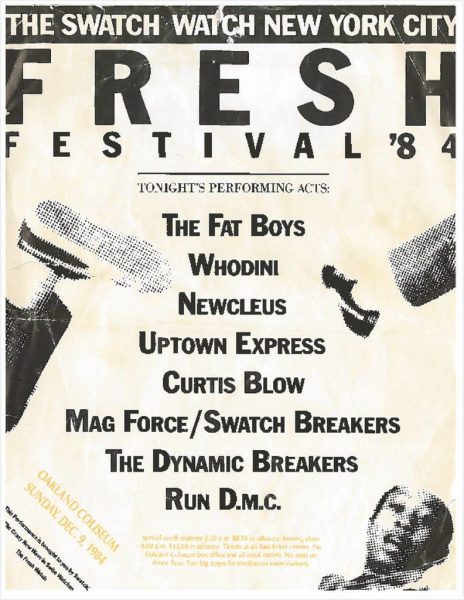

AH: The 1984 Fresh Fest Tour, featuring Run DMC, Fat Boys, and Kurtis Blow, was hip-hop’s 1st big money-making tour and an international success. It was one of the first of its kind. And YOU produced this! This is known to be one of the 20 greatest hip-hop tours of all time. How did this come together?

CW: I was physically hitting every city in the U.S. as the Jackson Tour Marketing Director. I had a front row seat to the underground phenomenon. Night clubs and skating rinks were booming hip-hop songs. Kids were break dancing in the streets, and radio and TV were largely ignoring it. I made a decision to put together an experience of non-stop dance music never seen before. With entertainment, it has to connect. It has to communicate with the audience and it has to reflect the culture.

AH: I’d love to hear about the top-grossing play you and your team produced and promoted, called “A Good Man is Hard To Find.” How did you get this production going and where did the success of this experience lead to?

CW: It started with a series of gospel plays that reflected the social ills that plague our community. A play called “Mamma Don’t,” about mothers with addictions raising kids and another called “Wicked Ways,” about teenagers getting sucked into gang violence. They were produced seriously, but humorously. We were packing theaters with them. The one I got involved with most was “Wicked Ways.” One night the police department came to me and said, “What are you doing? You’ve got a theater packed with drug dealers and church people, this is abnormal for gospel theater. What messages are you giving them?” I said, man, it’s about the community, they might be doing wrong, but they understand the treachery of what they do. After those plays a colleague introduced me to a new play needing to be financed and produced called a “Good Man Is Hard To Find.” I jumped right on it and that’s how we generated the money to start the Circus. It was there that I saw the need for Urban Family Entertainment. I saw whole families. Mothers, grandmothers, fathers, sons, grandsons, and daughters all on the same row. I asked the playwright, “How are we attracting whole families to a gospel play?” He said, “Because they can see themselves on the stage. We are showing them a reflection of their lives.” It was there that the idea was born and the funds were generated to start the Circus.

AH: Let’s chat through UniverSoul Circus. Over 25 million people have gone to the shows, with 14,000+ shows performed. 28 years of fun experiences, It’s the perfect mixture of everything you’ve done up to this point. Can you give us background into the creation of UniverSoul?

CW: I was the luckiest man alive and my mother used to always say I had nine lives, so I always believed it. The circus started a fire inside me. I knew that family had to be the centerpiece. I had done all these concerts, plays, and I was looking for how to put that together and appeal to a family. I went to the library and started studying Black entertainment from the turn of the century. I was still working on the plays in New York and I was at a festival, more of a retail type festival for Black History Month. And I saw a booth that said “Africans and Circus Rings”. And this guy had all the history of Black participation in the circus. And I knew right then that idea was from a power deeper than me.

CW: I took all the money I made from the plays and lost it with the first show and all the investors ran! But what I learned was the difference between a concert and a family attraction. I studied attractions and how long it takes for them to break even and how much patience you have to have to develop one. When I lost, I lost everything. I wasn’t afraid, it didn’t scare me. What drove me was the customer and the reaction of the consumer. They were all really excited about it, but my problem was marketing it to them.

AH: Wow, tell us a little bit more about the programming and what a show would look like?

CW: I actually went to Sarasota and immersed myself in the circus world. We drove the culture and it was very positive. The circus has always been about positivity, movement, and celebration of Black culture from a global perspective. We looked at sports, spirituality, humor, success stories of African Americans, and we had music from all genres. The circus is made of young people and is driven, or has the undertones, of hip-hop culture in terms of fashion, style, swagger. All these things are embodied by all races and cultures—Chinese, Russian kids, and more. The circus has always been a global art form and it’s always been made up of people from around the world.

“What we’ve done is cool, but it signifies where we can go. It expresses who we are and what we can do. We’re an innovation company.”

AH: How has UniverSoul changed throughout the pandemic?

CW: It’s devastating to our business, but also there’s opportunity. Time to reflect. It’s given pause to really think about the future. What we’ve done is cool, but it signifies where we can go. It expresses who we are and what we can do. We’re an innovation company. We’re looking forward to continuing with our history of innovation. In terms of a pivot, we created a model where we took the walls away and just used the top and we created socially distanced seating to be very minimal. We are excited that we’re prepared now with a model that we can move safely as our industry rebounds.

AH: Can you tell us about UniverSoul Cares? You seem to have the common thread of philanthropy in your projects.

CW: Well, the program started as necessity is the mother of invention. We really needed to get our product into the community. In doing that, we started getting involved in the community in give back programs. One of our first projects, Tickets For Kids, was a partnership with Ticketmaster that started in Atlanta in ’94. We have a Food for the Soul program where we collaborate with schools collecting food for food banks in exchange for free tickets. Then we started working with the homeless families, which led to free shows for them. We teamed up with Hosea Feed the Hungry in Atlanta, Chance the Rapper, 100 Black Men of Chicago, and the homeless shelter community in New York. We’ve done scholarship programs across the country, donated computers, the list goes on, It’s a natural part of us.

AH: That’s really beautiful. Where do you see all of this going in the future? As you’ve had this time to slow down and really think about what’s to come, what do you see?

CW: I have enough ideas to last my entire lifetime and beyond. I’d like to explore the richness of our culture and how it interacts with the world. It’s not about just a Black thing. It’s about how the culture interacts on a larger scale and the authenticity of that. That’s what we’ve done with the Fresh Festival, that’s what we’ve done with UniverSoul Circus. Understanding your product from the roots. Our culture is so rich and there’s so many things that we can do. You’ll hear from us. The Commodores always said, “We’re headed to the woodshed.” Well we’re in the woodshed, formulating our ideas and focusing.

AH: You have so many people championing your success, including myself. Is there anything you have to say to your fans today?

CM: Really to stay tuned! We’ve got some new ideas on the horizon that we’re looking forward to launching and they’re different. They’ve never been done before and are very exciting. So stay tuned because we’re going to deliver. We’re going to deliver some exciting stuff, new things are coming in the future from UniverSoul!

AH: Cedric, thank you for your time. We look forward to the next iteration.